Go Back Go Back

Print Page Print Page

A Brief History of the Video Projector

A Brief History of the Video Projector - Part 1 of 3

Moving Pictures

Phenakistoscope Plate circa 1893, created by Eadweard Muybridge

Another mechanical animation device was the Zoetrope. First seen in Europe in 1834, the Zoetrope was invented by William Horner. The Zoetrope is essentially a spinning drum with pictures painted on the inside of a narrow paper insert. The insert was set in the drum which would be persuaded to spin. Peer through one of the slits provided and, just like the Phenakistoscope, people or animals could be seen to move.

Modern recreation of Victorian Zoetrope, Photograph © Andrew Dunn

Persistence of Vision

These early moving picture devices worked because of a phenomenon known as persistence of vision. Your eye is not a camera. It doesn’t have a shutter or see in frames. The theory says that an image is actually retained in the retina for a moment. The next image, slightly different than the first, blurs with the first image (in the case of motion pictures) and so on. Strung together your brain “sees” this as smooth motion. Modern displays deal with source material that has anywhere from 24 to 60 frames per second, but the principal remains the same: change the pictures fast enough and they appear not as still pictures, but as a naturally moving object.

Spin a Phenakistoscope or Zoetrope faster and the motion becomes more fluid, less jerky. Your brain is a marvelous thing, and uses something called Persistence of Motion to blend these still images into a moving one. One of the first examples of this most of us were introduced to were picture flip books. Or even the stick men you drew on the bottom outside page corners of you English book. Flip the pages and the images will blend together and take on a life of their own. Modern devices like HDTVs, HD Projectors, etc, are better at reproducing the images, but still use the same principals established with these oldest of motion picture devices. By taking or drawing pictures sequentially, over time, and showing those pictures in the same order quickly enough, your brain is tricked into perceiving these still pictures as having motion. The same is true of film and video cameras – they don’t actually capture motion. Instead they break motion down into single pictures that, when displayed sequentially, have the appearance of motion.

Eadweard Muybridge, the Zoopraxiscope, and “The Matrix”

In 1879, Eadweard Muybridge solved a very basic limitation of the Phenakistoscope, audience size, by placing a lantern behind the spinning disk to provide illumination. A lens was required to focus the light, and adjusted just so, the images could take life on a wall, curtain, anything. Muybridge decided that this marvelous new invention should be called “The Zoopraxiscope”. The Zoopraxiscope was similar to the Phenakistoscope in that they both used illustrations to convey moving images. Like the Phenakistoscope it had sequential drawings placed around the edge of a glass disk, but unlike the Phenakistoscope, or anything else that came before it, large moving images could now be shown to a large group of people. . Muybridge made experiencing these new moving pictures a social affair. In inventing the Zoopraxiscope, he had also invented the projector, in its most primitive possible form, but a projector none-the-less.

Zoopraxiscope, Courtesy Kingston Museum

Zoopraxiscope disc “Mule Bucking and Kicking”, by Eadweard Muybridge, courtesy of

Kingston-on-Thames Public Library

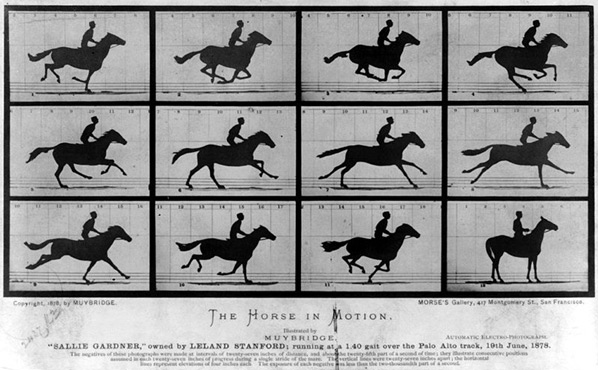

Eadweard Muybridge also pioneered a method of achieving motion photography using still cameras, allegedly to settle a $25,000 bet for politician and industrialist Leland Sanford. Sanford maintained that during a horse’s travel, there came a moment when all four of a horses hooves were in fact off the ground. This was called “unsupported transit” and was a popularly debated question at the time. Muybridge settled Sanford’s question using a single photographic plate containing sequential photographs of Sanford’s horse, Occident, demonstrating “unsupported transit” during a trot.

“The Horse in Motion” by Eadweard Muybridge,

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Muybridge went on to use his technique to photograph a variety of animals and mostly-nude people performing tasks, like walking down stairs, boxing, even a child walking with his mother. Nude. 100 years later a similar photographic technique was used for “bullet time” in the “The Matrix” Trilogy. Muybridge arranged his cameras in a row, while in “The Matrix” the cameras wrapped around the subject. What the Wachowskis had that Muybridge didn’t were the computers to stitch the frames together.

But while Eadweard Muybridge’s Zoopraxiscope established the projection concept, it would be others who would improve upon the design.

Victorian Cinema

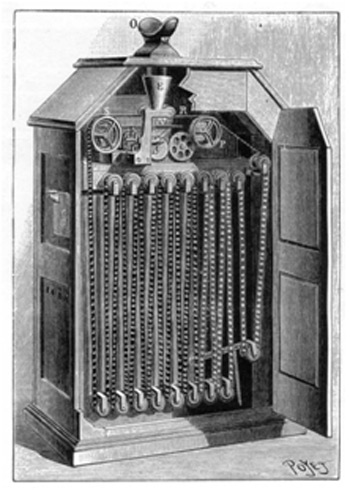

1889 - William Dickson worked under Thomas Edison. Now, most would tell you Edison was a bit of a megalomaniac and people didn’t like working for him. Regardless, Edison was signing the paychecks of William Dickson when Dickson invented an incredibly complicated, hard to use device, called the Kinetoscope. Instead of pretty drawings of boxers and horses, Dickson’s Kinetoscope used photographs, pictures of real people and things. Edison was apparently spurned on after seeing Muybridge demonstrate the Zoopraxiscope. It seems natural enough, given Edison’s involvement with photography equipment, that he would see the potential of using photographs instead of glass paintings. The Kinetoscope used long filmstrips run through a series of sprockets, enclosed in a wooden cabinet. The filmstrips were viewed through a window (or “peephole”) in the top of the cabinet.

Edison’s Kinetoscope, circa 1894

Edison’s Kinetoscope, circa 1894

Given the times, image quality was impressive – the pictures moved! Kinetoscopes quickly became the standard for displaying moving pictures, in spite of the fact that they were single person view devices – the peephole allowed only one viewer at a time. Kinetoscopes weren’t for public display, but for public consumption. Edison had more or less turned the projector in on itself - each Kinetoscope could be used by only a single viewer. Kinetoscope parlors opened up, with Kinetoscopes arranged in rows. It was Edison producing most of the material shown as well, making him one of the first movie moguls.

|