Go Back Go Back

Print Page Print Page

A Brief History of the Video Projector

A Brief History of the Video Projector - Part 1 of 3

Young Griffo vs Battling Charles Barnett

San Francisco Kinetoscope parlor, circa. 1894–95T

The purpose built camera developed to take advantage of the Kinetoscope was called the Kinetograph. Like the Kinetoscope, mechanical movement of film by sprockets was critical. It allowed each frame of file to be exposed the correct order for the exactly correct amount of time. Film would be taken from the Kinetograph, developed, and used immediately in the Kinetoscope. Given that it was the size of a small car and non-moveable, the Kinetograph is worth noting because it was housed in a special building with a hinged roof, and set on a track so the building itself could rotate to catch the light.

The Kinetoscope is important because it combined for the first time many of the hallmarks of modern film projectors – a perforated film strip bearing sequential images, sprockets to move the film over the light source, and a high speed shutter to light each frame individually as it passed over the light source. Not only was the Kinetoscope a mechanical marvel, it featured an electric motor and electronically driven sprockets. It just didn’t project the image in any way.

Woodville Lantham and his sons found the Kinetoscope to be very impressive. They’d heard the grumbling, and decided there was a real market in developing a film projector. The piece they developed is widely considered to be the first film projector used for commercial exhibit. The film was Young Griffo v Battling Charles Barnett “, a boxing match that had been shot on the roof of Madison Square Garden two weeks earlier. Woodville decided the best name for his new film projector was “Eidoloscope”, and so it remained for a few years when it was changed to “Panoptikon”. Because they could cater to larger groups, the cost of a single Eidoloscope could be spread out over more people. Wear and tear was also significantly decreased over the Kinetoscope, again, given economies of scale involved. Eidoloscopes were much more profitable as a result.

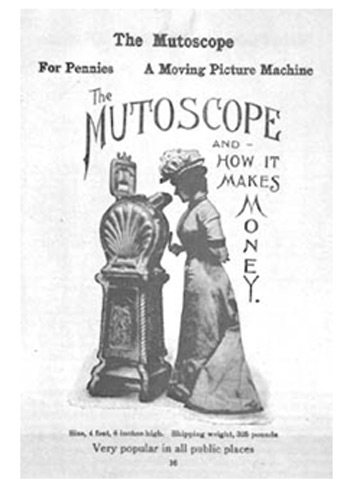

Dickson reportedly did some work on the Eidoloscope for Lantham and Sons while still employed by Edison. Dickson also put Lantham in touch with many of Edison’s disgruntled ex-employees, who also contributed time and expertise to the project. Edison had a knack for finding new talent, hiring them, and pissing them off so much many of them went on to other, more profitable ventures, like competing directly against him. After finally parting ways, Dickson went on to work on the “Mutoscope”, a new “peep-show” device that used a “flip book” type device.

Mutoscope trade advertisement from 1899

Mutoscope trade advertisement from 1899

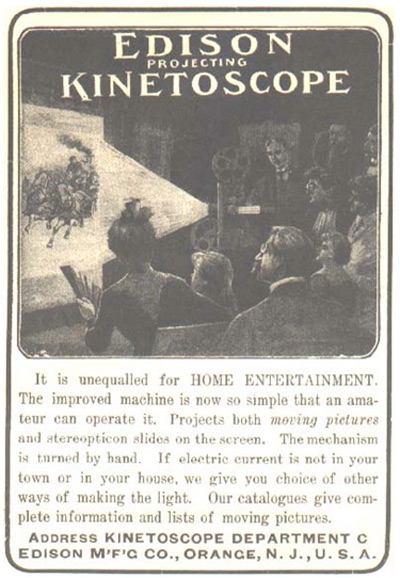

With Dickson’s departure, Edison was at a bit of a loss and was falling behind – he’d had much success with the Kinetoscope and didn’t feel the need to expand the technology, so he returned to a tried and true formula – buy someone else’s invention and take credit for it. Edison purchased the Phantoscope from Charles Frances Jenkins and Thomas Armat. He renamed it the Vitascope. The Vitascope allowed for large moving image projection. Never able to take advantage of the Vitascope, Edison scrapped it for another of his “inventions”, the very complicated Projecting Kinetoscope. Anticipating the market by several decades,

Edison also introduced a very ambitious and very expensive Home Projecting Kinetoscope in the early 1900’s. The Home Projecting Kinetoscope used short film sequences loaded into cartridges. It, like other projection devices of the time, was an incredibly finicky, complicated machine and proved to be too ambitious to really take off.

Newspaper ad for Edison's Projecting Kinetoscope, published circa 1900–10

With time, other film projectors were invented and discarded. Again, they shared common features, some executed a little differently, but were similar in form and function. These new projection devices allowed large groups of people to sit and watch a motion picture, the same motion picture, together, at the same time. The experience we’ve come to know as “going to the movies” has largely been in place since the late 1800s. It was only a matter of time before people began looking for a practical way to bring the experience home. But there were a few big steps left to make.

Sound

For a long time moving pictures had no integrated sound. Any modern enthusiast will tell you that sound is at least half, if not more, of the cinema experience. Up until the early 1900’s, sound was provided by a lonely pianist, full orchestra, or anything in between. Dialogue was comprised of on-screen cue-cards, presented while the villain twisted his moustache. Ah the golden age.

What was lacking was a reliable method of recording and playing back audio that would be synchronized to the on-screen action. The best audio technology of the day was a phonograph that played back music recorded on wax disks or tin drums. Even assuming you could synch a phonograph to a motion picture, phonographic records were often no longer than a few minutes, too short for a full length feature. As well, given that phonographs of the time had no electronic amplification and reproduced sound by using a large horn to magnify the vibration of a small diaphragm, sound pressure levels were quite limited, making phonographs useless for large audiences.

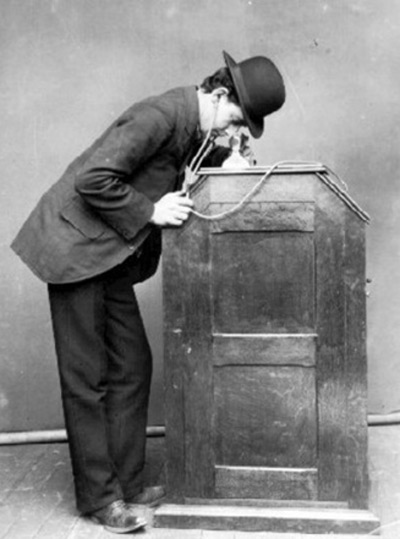

We’re getting a little ahead of ourselves – the current state of the art “projection” system, the Kinetoscope, wasn’t a projector at all. It was a one viewer peep hole device. A winning formula proved to be to shoe-horn the best audio technology, the phonograph, into the cabinet of best moving picture technology, the Kinetoscope. Amplification wasn’t required given that it was a single user system, and Kinetoscopes were already a proven winner. In 1894 William Dickson and the rest of Edison’s company began working on a way to synch phonograph playback with a Kinetoscope moving picture. The result? The Kinetophone. The recording was timed to the picture and had to be reset by moving the needle back to the beginning of the recording. The user wore rubber ear tubes to hear the action, while peeping through the peep hole.

Publicity photograph of future chiropractic patient using Edison Kinetophone, circa. 1895

Like its predecessor, the Kinetoscope, the Kinetophone was limited in that only one person could use it at a time. Aside from being truly uncomfortable to use for long periods, it was a complicated device, very delicate and prone to going out of synch. Early development of the Kinetophone stopped when Dickson and Edison had their final falling out - Dickson left the company to build the Mutoscope. It took another 18 years for Edison to redesign the Kinetophone.

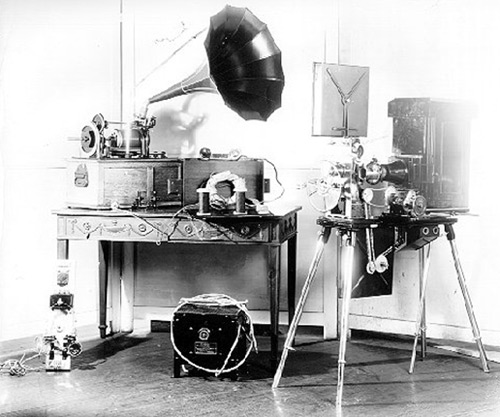

In spite of the limitations, talking motion pictures continued to be made. By 1914, the Kinetophone had evolved into a complicated pulley driven contraption to synch the speed of the film with that of the sound recording. Edison finally gave up in 1915. The Kinetophones were quirky and hard to use, and film duration was short, limited by the length of the phonograph recording. Operators at the time were never trained properly in its operation and maintenance, leading to a variety of problems. Because of the poor quality, audiences were not impressed and attendance was less than impressive. Good sound blending seamlessly with good picture was proving a hard nut to crack.

Edison Kinetophone circa 1913, from Edison NHS

But the ball had been set in motion. Audiences had their collective appetite whetted and were looking to be entertained with bigger, better sound, and innovators were looking to capitalize. In France, Ian Gaumont developed a technology similar to the Kinetophone with his Chronophone. German Oskar Meester designed the Biophon system which saw use in 500 German theaters by 1913. Electronic amplification was “borrowed” from early telephones, but was crude and quiet, even by standards of the time. The complexities of the mechanisms involved meant that most “talkies” were short subjects, or had brief moments of sound in longer features.

A tipping point had been reached, however, and soon there would be no turning back. In 1925 Sam Warner of Warner Brothers was introduced to a new sound –on-disc system that would revolutionize the cinema experience.

|