Go Back Go Back

Print Page Print Page

A Brief History of the Video Projector

A Brief History of the Video Projector - Part 1 of 3

Vitaphone

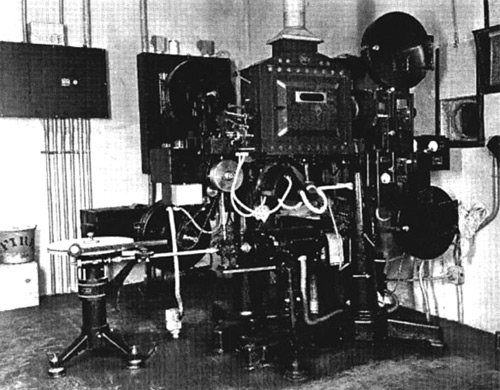

Vitaphone projector and player system. Turntable is visible at the rear of the machine. Courtesy The Vitaphone Project (http://www.picking.com)

The Vitaphone was originally developed by Western Electric on behalf of Bell Labs. The technology was purchased in 1925 by Sam Warner at Warner Brothers. Wasting no time and taking an enormous financial risk, Warner Brothers introduced the Vitaphone to audiences in August of the following year. Other studios had had the opportunity to purchase the technology, but had passed given the cost of transitioning from silent movies to “talkies”. The costs associated with the transition to sound was enormous. - few theaters studios were equipped for sound, and many of the silent film era’s top stars were locked into long term contracts.

The first film publically shown with the new system was “Don Juan” starring John Barrymore. “Don Juan” featured a full musical score and sound effects, but included no dialogue. It wasn’t until the 1927 release of “The Jazz Singer” that film going audiences would experience a complete soundtrack with fully synched dialogue. It’s a classic story of loss and redemption, and a perfect framework to introduce a new era of film making and viewing. It featured Al Jolson as Jackie Rabinovitz, and a whole soundtrack of music delivered in Jolson’s unique style. The film was a huge success and firmly entrenched the concept of talkies in the minds and wallets of American filmgoers. That Jolson delivered much of the film in “black face” is the subject of another article.

Audiences went crazy, firmly entrenching the concept of “talkies” into public consciousness. Sam Warner had gambled and won.

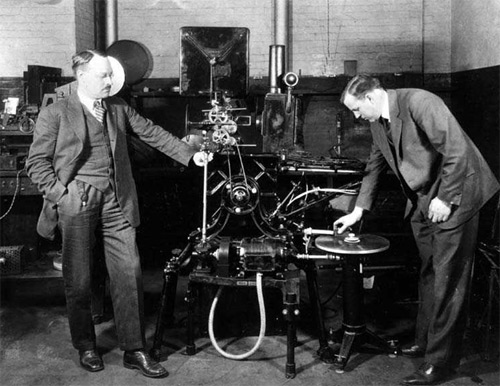

Sound-on-disc demonstration, ERPI/Warner Vitaphone

Warner Brother’s Vitaphone was a highly functional sound-on-disc system, with a phonograph at its heart. The phonograph was synched to the projector by a mechanical interlock. The projectionist would align a start mark on the film strip with a start mark on the phonograph. Instead of a traditional horn system to amplify the sound, the Vitaphone used new amplification technology in the form of the Audion vacuum tube, developed by Lee De Forest.

The Audion tube was a significant improvement over existing “magnifiers” of the time, because the Audion could actually take weak electric signals and amplify them. De Forest wasn’t entirely sure how it worked, but the fact was it did work. De Forest had originally developed the Audion for use in his Phonofilm sound-on-film system, which he worked on with Thomas Case. More on that later. In the early 1920’s, the chief advantage of the Vitaphone system was fidelity – it sounded better than competing sound-on-film systems, at least until the wax discs wore out.

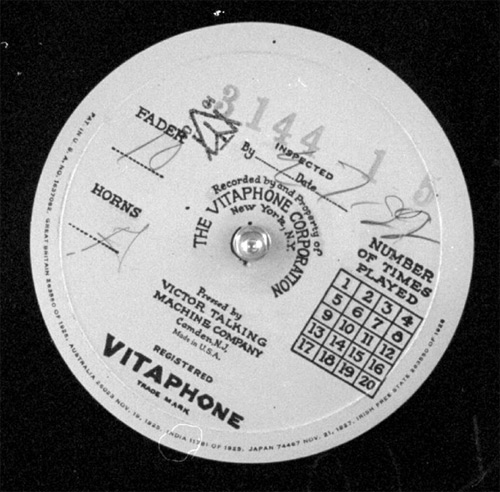

Vitaphone disc label from AT&T exhibit "Dawn of Sound"

The sound was played back from 16 inch discs playing on a phonograph at 33 1/3 rpm to match the 11 minute run time of the 1000 foot film reels used at the time. The projectionist would change the phonograph disc when changing the film reel. The disks themselves were large and prone to breakage, lasting typically only 20 screenings before needing to be replaced. Like other phonograph systems, the Vitaphone had severe synchronization problems. If the record skipped the projectionist would have to manually re-set the phonograph needle. If the film print became damaged and not properly repaired the Vitaphone could lose synch as well. Engineers included special levers to retard and advance timing slightly but this required constant care from the projectionist.

Because of these drawbacks, as well as improving performance from sound-on-film technologies from other studios, Warner Bros stopped using the Vitaphone in 1930. To that point though, Warner Brothers produced 2,000 films and shorts using the Vitaphone system. Limitations with the Vitaphone were primarily mechanical in nature; developers at the time had opted for a brute force approach by mechanically locking the speed of rotation of the phonograph disc with the movement of the film. With regular wear and tear, film prints would inevitably vary in length, getting shorter as damaged sections were removed. As well, records could skip or get scratched, and, unlike film stock, the wax audio discs could not be edited for length.

As a result, the Vitaphone ultimately failed because the sound was completely separate from the picture. What was needed was a new, electronic approach to the problem. Luckily enough, Lee De Forest wasn’t finished yet.

|