Go Back Go Back

Print Page Print Page

A Brief History of the Video Projector

A Brief History of the Video Projector - Part 1 of 3

Lee De Forest and Phonofilm

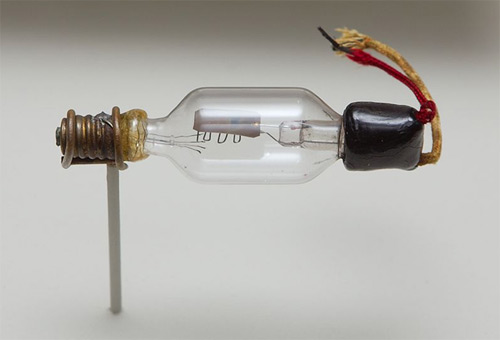

De Forest’s Audion Vacuum Tube, taken at “The History of Audio:

The Engineering of Sound”, copyright Gregory F. Maxwell

De Forest was the first to file a patent for a “sound-on-film” technology. Competitive systems of the era, like the Vitaphone (still in development in 1919), were largely “sound-on-disc” devices, which were essentially variants of Edison’s projecting Kinetophone. Sound-on-film attempted to entirely eliminate audio synch issues by embedding the film’s soundtrack onto the film itself. Each frame of film would have the exact picture and sound information for what was occurring in that frame. If (and when) the film strip became damaged and frames had to be removed, perfect audio and picture synch could be maintained. De Forest called his system Phonofilm.

Phonofilm film strip showing audio information encoded beside the film frame

Sound on film literally encodes audio information directly onto the same film strip as the picture frame. Film stock aspect ratios and sizing was adjusted to make room for the audio track. Pioneered by Eugene Lauste, sound was captured by a microphone and translated into sound by a device called a “light valve”. The light valve was a small resonating piece of metal over a small slit. Sound reaching the metal would be translated into sound by the vibrations of the metal, then photographed onto the film. From an engineering standpoint it was very much the solution to a problem. To your ear however, it didn’t sound so great. So while Phonofilm solved the synch problems rampant with sound-on-disc systems, fidelity suffered in comparison. Overall opinion on the systems seems to say that even given the standards of the time Phonofilm’s sound-on-film process was poor sounding. Quality offered by early sound-on-film technologies like Phonofilm was poor because sound-on-film relied on relatively sophisticated optical and electrical solutions, and electronics of the 1920’s was anything but cheap and reliable.

De Forest improved the technology using patents and techniques gained from a short lived collaboration with Theodore Case, another early inventor. Phonofilm was important because De Forest and Case were the first to patent the concept for what was, at the time, a shaky concept using new, untried techniques. Theodore Case’s short relationship with De Forest and Phonofilm was due to De Forest taking credit for Case’s patents and hard work. De Forest was also in the habit of suing prior collaborators. Case went on to work for William Fox, at Fox Studios. Fox bought Case’s patents, the patents of another De Forest Collaborator (and suing victim) Freeman Harrison Owens, along with the US rights to some European technology. This combination of people and talent would be enough to set the tempo (no pun intended, I swear!) for the sound-on-film processes that would remain in wide use even today. Fox championed a “variable density” optical track, Movietone. RCA debuted their “RCA Photophone”; it used a “variable Area” optical recording system. In 1930, Warner Brothers, sensing the direction the wind was blowing, abandoned their Vitaphone in favor of the RCA Photophone.

And so more pieces fell into place. By 1928 most of the major innovations were in place – Edison’s steel sprocket transport mechanism from the first Kinetoscope, Lee De Forest’s Audion, which for the first time truly amplified weak microphone signals, to Theodore Case and Freeman Harrison Owens who improved the sound-on-film process, and made movie sound simply sound better. Audience reaction? Ecstatic. Not only were the words actually coming in perfect synchronization with the characters lips, the words, soundtrack and sound effects sounded good too.

Dreaming in Technicolor

Lacking in American films to this point was true color. Film had finally been synched to sound, which in turn could be shown to a large group of people, but everything was in black and white. Among the first to crack the color nut was Technicolor. Technicolor had first added color to short motion pictures way back in 1917. Then, “Technicolor Process 1” as it was called, was a two color system, red and green. Technicolor Process 1 used a combination of black and white film stock, red and green filters, and a prism to combine the red and green images. A single film, “The Gulf Between” was shot using Process 1. In 1922, Technicolor introduced Process 2 as an improvement on the original Process 1. Like Process 1 Process 2 utilized a prism and filters to add red and green to the film projected, and special tinted film stock and layered the colors together in the projector. The first film released using the process was 1922’s “The Toll of the Sea”. Other films to use the process were “The Ten Commandments” in 1923, “Wanderer of the Wasteland” in 1924, the original “Ben-Hur” in 1925, and Douglas Fairbanks’ “The Black Pirate” in 1924.

“The Toll of the Sea”, Technicolor Process 2, 1922

It was a complicated process – the film stock was thin and prone to breakage. Because the process involved layering two strips of film the film would occasionally flex and separate, creating spots of soft focus. All in all, like the Kinetophone, it was a technology that proved too complex to be cost effective.

Process 3, introduced in 1928, was designed to eliminate most of the point of projection problems associated with Process 2. It utilized the same camera, but used a process called dye-imbibation to color the film print and eliminate the double prints found in Process 2. The first film made using Process 3 was “The Viking” in 1928. The first all talking motion picture filmed in Technicolor was 1929’s “On with the Show!”

It’s hard to imagine studios weren’t beating each other up over the first color film cameras and film stock, but they weren’t. There had been a lot of investment in current, black and white technology, and most cinematographers didn’t know how to use color film. So, when The Great Depression hit late in 1929, shooting films in an expensive new format was low on the list of priorities. To entice film studios, Technicolor introduced its first three strip color process. Like older systems, the process reproduced red and green, but for the first time also included blue. The prints were produced using a dye transfer process. Early tests were so impressive Walt Disney bought exclusive 2 year rights to the process.

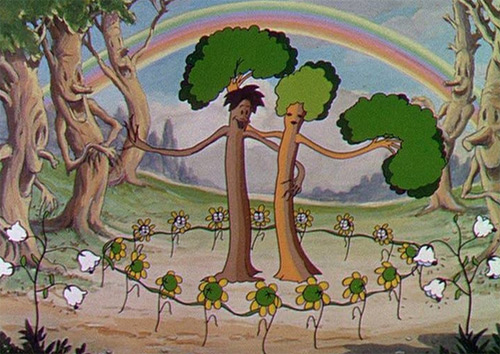

The first film produced using Process 4 was Disney’s “Flowers and Trees” in 1932, and won an Academy Award. The new process lent itself more to producing animation as each frame would be photographed three times – once for red, once for green and once for blue, then dye was transferred to the film strips, creating rich vivid colors. It was a winning formula, but it was an expensive one. Technicolor was a complicated process, and it took some time to convince Hollywood of the 30’s it was worth the added cost.

Walt Disney’s “Flowers and Trees”, 1932

The first full length film made with 3 step Technicolor was “Becky Sharp” in 1934. The commercial success of later color films, “The Trail of the Lonesome Pine” in 1936 and “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” in 1937, cemented the new technology in the hearts and minds of Hollywood producers. Audiences were responding favorably to Technicolor films, but there had yet to be that one, great breakout success that would burn itself into the American consciousness. That success came in 1938 with the premiere of the first great commercial Technicolor success, “The Wizard of Oz.”

And so all the major pieces fell into place - Talkies, where dialog and music were perfectly, reliably, synchronized with full motion images, replaced silent movies. Motion pictures were in rich, spectacular color thanks to the hard work of dozens of dedicated researchers. Movies had finally become cinematic. However, a whole new shootout was about to erupt.

Go To Previous

Stay tuned for Part 2 of the History of Projection. Coming soon...

|